Lebanon In need of new energy

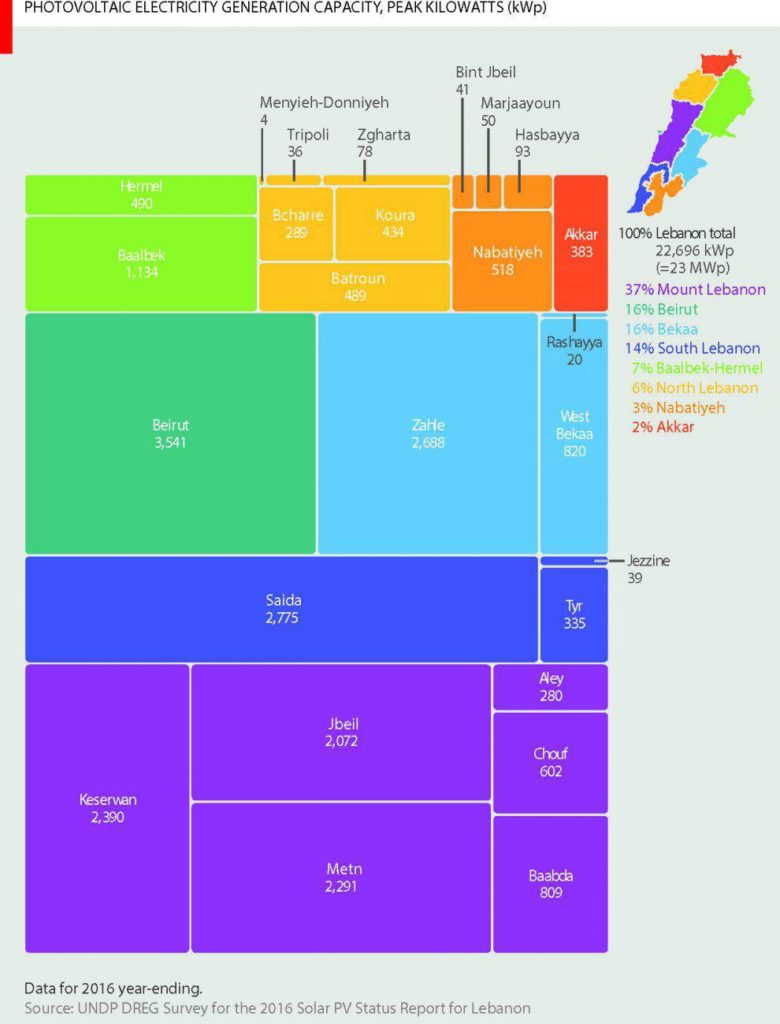

The plan is to build 12 solar plants across four districts of Lebanon—three each in South Lebanon, Mount Lebanon, the Bekaa Valley, and North Lebanon.

استعادة كلمة المرور الخاصة بك.

كلمة المرور سترسل إليك بالبريد الإلكتروني.

The plan is to build 12 solar plants across four districts of Lebanon—three each in South Lebanon, Mount Lebanon, the Bekaa Valley, and North Lebanon.

القادم بوست

استعادة كلمة المرور الخاصة بك.

كلمة المرور سترسل إليك بالبريد الإلكتروني.

التعليقات مغلقة، ولكن تركبكس وبينغبكس مفتوحة.